New York slavery era revealed

By David Ho

NEW YORK - In a city known for fighting to abolish slavery, there is another story: the tale of the slaves who built the road that became Broadway and the wall that named Wall Street.

"When most Americans think about slavery, they think about 'Gone with the Wind' and cotton plantations in the South immediately before the Civil War," said Richard Rabinowitz, curator of the "Slavery in New York" exhibit that opens Friday at the New York Historical Society. "This exhibit breaks new ground because it focuses on slavery in the North," he said. "Most people really don't know that story. It's going to come as a great shock." The exhibition, set to run through March 5, is the largest for the 201-year-old historical society and one of the biggest ever devoted to slavery. The 9,000-square-foot project includes about 400 historical objects, documents and re-creations, along with multimedia and interactive displays.

A rare handwritten draft of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation will be displayed through Oct. 15. Across nine galleries, the exhibit spans the period from the early European settlements of the 1600s to 1827, when New York abolished slavery. In between are British Colonial times when one in five New Yorkers was an enslaved African and the city's slave population was second only to Charleston, S.C. "New York had slaves longer than it's had freedom," Mr. Rabinowitz said.

The society's 18-month slavery project also includes lectures, tours and programs for children. A second exhibit to open by early 2007 will explore New York's central role in both fighting and funding slavery in the decades leading up to the Civil War and Reconstruction. "The investment in slave labor and slave trading built many of the fortunes of the city," said James Horton, the exhibition's chief historian.

Mr. Horton said New York's elite were so financially involved with Southern plantation slavery just before the Civil War that city officials considered having New York City secede from the United States along with Southern states.

A surge of scholarly interest in New York slavery began in 1991 after construction workers in Lower Manhattan unearthed an African burial ground dating from the 1700s. About 400 sets of remains were removed for study and were reinterred in 2003. A permanent memorial is planned for the burial ground, now designated a historic landmark.

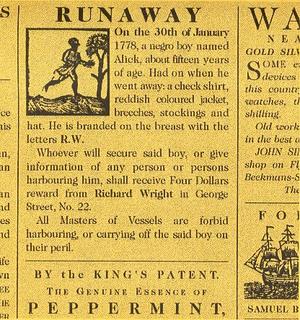

The historical society began work on its exhibit a year ago, using its large collection, which includes paintings, abolitionist documents, ads seeking runaway slaves and coroner reports stemming from a 1712 slave revolt.

The exhibit also includes wire sculptures of slaves that the society describes as evoking "the toil of the faceless, voiceless peoples whose histories were [nearly] erased." Among the first displays are materials from when New York was still the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam. One document describes the Colonial governor granting "half-freedom" to 11 slaves, who later created the first free black community in North America in the areas of Manhattan now called Greenwich Village and SoHo.

Under British control, the slave population grew, and ultimately about 41 percent of New York households owned slaves. Typically one or two slaves lived in a home, staying in basements, attics or backyard kitchens. The small groupings often broke up families, separating mothers from children. Although the treatment of New York slaves varied, overall living conditions were terrible and the labor extreme, Mr. Rabinowitz said. He said slave food in New York was likely worse than on Southern plantations and often led to malnutrition.

The exhibit also chronicles the period's growing slave trade with an electronic version of a trading book from the ship "Rhode Island." Visitors can explore the book's entries, which describe how it sailed from New York in 1748 loaded with items such as butter, cheese and rum to trade with merchants along the African coast for manufactured goods such as guns and pots and pans. The crew then traded for people and sailed back with 124 slaves; 38 died on the way.

Displayed advertisements from New York newspapers announce the new "Negroes to be sold." One of the men behind the sale, Philip Livingston Jr., went on to sign the Declaration of Independence. Another gallery focuses on the American Revolution and the years after the British captured New York in August 1776. More than 10,000 slaves fled to the city seeking freedom behind British lines and many joined them to fight the American forces.

When the British left, more than 3,000 slaves went with them, including Deborah Squash, who in British documents is listed as a former slave of George Washington. "At the end of the war, fearing that Washington and others -- which is a realistic fear -- would come back and try to reclaim her, she went with the British troops off to Nova Scotia to a new life in freedom," Mr. Rabinowitz said.

New York began a gradual emancipation with restrictions in 1799, but the shift to abolition was much slower than in other Northern states with smaller slave populations. Some forms of racism also worsened as the free black population grew.

The exhibit shows the role of black New Yorkers in the abolitionist movement and how freed slaves became entwined in public life, building homes and forming churches and schools. One gallery is devoted to the celebration after the abolition of slavery in New York on July 4, 1827, and includes a panoramic display of a Broadway parade.

A final section explores why this history is not well-known and how the South became identified with slavery and the North with freedom.

Nearby, visitors can record video messages about their exhibit experience that become part of the show.

"Slavery was not a sideshow in American history. It was the main event," Mr. Horton said. "That's the story we want to tell."

Source: Cox News Service

1 Comments:

Interesting! As much as I'd like to think I know about Manhattan I had no idea about this. Great research!

Post a Comment

<< Home