Comedian Richard Pryor Dies at 65

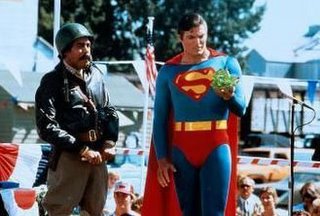

Pryor and the late Christopher Reeve from "Superman III"

Pryor and the late Christopher Reeve from "Superman III"December 10, 2005, 5:04 PM EST

Richard Pryor, whose blunt, blue and brilliant comedic confrontations confidently tackled what many stand-up comic's before him deemed too shocking—and thus off-limits—to broach, died this morning. He was 65. Pryor suffered a heart attack at his home in San Fernando Valley section of Los Angeles early Saturday morning. He was pronounced dead at a nearby hospital.

The comedian's tremendous body of work, a political movement in itself, was steeped in race, class, social commentary, and encompassed the stage, screen, records and television. He won five Grammys, an Emmy and was an Academy Award nominee for his role in "Lady Sings the Blues" in 1972. At one point the highest paid black performer in the entertainment industry, the highly-lauded but misfortune-dogged comedian inadvertently became a de facto role model—a lone wolf figure whom many an up-and-coming comic from Eddie Murphy and Chris Rock to Robin Williams and Richard Belzer—have paid due homage. Pryor alone kicked stand-up humor into a brand new realm. "Richard Pryor is the groundbreaker," comedian Keenan Ivory Wayans once said. "For most of us he was the inspiration to get into comedy and also showed us that you can be black and have a black voice and be successful."

Pryor had a history both bizarre and grim: self-immolation (1980), heart attack (1990) and marathon drug and alcohol use (that he finally kicked in the 1990s). Yet Pryor somehow—oftentimes miraculously it seemed—continued steady on the prowl, even after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1986, a disease that robbed him of his trademark physical presence. Both verbally potent and physically eloquent, Pryor worked as an actor and writer as well as a stand-up comic throughout the '70s and into the '80s. He won Grammys for his groundbreaking, socially irreverent, concert albums "Bicentennial Nigger" and "That Nigger's Crazy." And in 1973 he walked away with a writing Emmy for a Lily Tomlin television special.

Pryor starred in more than 30 feature films—from "Lady Sings the Blues" and the semiautobiographical directing turn in "Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life is Calling," to the less memorable "The Toy" and "Superman III." He also co-starred with comedian Gene Wilder in the highly popular buddy films "Silver Streak" and "Stir Crazy." It was however his concert films—particularly "Richard Pryor—Live in Concert" (1979)—which many critics consider to be his best work.

Called genius by some, self-destructive madman by others, Pryor, throughout the tumult of a zigzagging career, remained an inclement force of nature. "He was actually one of the rare people of that era who was a product of the chitlin' circuit, and the white, liberal, coffee shop thing," said journalist and culture critic Nelson George. "Where Bill Cosby immediately made it into the crossover realm . . . Pryor was a product of both. He was able to draw upon his kind of raw black experience through his storytelling skills, and that was accessible to a hipper white crowd. He mixed all of those things—but always had a singular vision. I think it's why he became such a huge star."

In 1975, Pryor appeared on "Saturday Night Live," at the time considered to be among TV's most irreverent shows. But it wasn't until Pryor went on the air that "SNL" instituted for the first time a five-second delay to ensure that Pryor did not ruffle the NBC censors. (Pryor also had his own short-lived series, "The Richard Pryor Show," which was axed after only four episodes in 1977, the victim of head office scrutiny and low ratings—he was pitted against the hugely popular "Laverne and Shirley" and "Happy Days".) In later years, Pryor's life was a blur of bad choices and reckless acts. Scarred by drugs, violence, quadruple bypass surgery, broken marriages and estranged children, Pryor, submerged in personal chaos, tried to take his own life.

The initial reports of June 9, 1980 were that the comedian accidentally set himself on fire while freebasing cocaine. Pryor finally revealed the truth in his autobiography "Pryor Convictions and Other Life Sentences" (Pantheon, 1995 and co-written with Todd Gold): "After freebasing without interruption for several days in a row, I wasn't able to discern one from the next . . . Imagining relief was nearby, I reached for the cognac bottle on the table in front of me and poured it all over me. Real natural. Methodical . . . I picked up my lighter . . . I was engulfed in flame. I was in a place that wasn't heaven or earth. I must've gone into shock because I didn't feel anything."

The freebasing incident, like many of Pryor's more dramatic mishaps, turned up as encore-worthy centerpieces of his stage routines. Among them, the much talked about New Year's morning in '78 when he repeatedly fired a .357 magnum revolver into his then wife's car. In incident after incident, the public repeatedly walked along side him, standing in full view of the wreckage, marveling at how many lives this mercurial man appeared to have. But Pryor was best known for his searing analysis about the state race relations. He was honored by the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts with the first Mark Twain Prize for American humor. "I feel great about accepting this prize," he wrote in his official response, his familiar edge glinting through, "I feel great to be honored on a par on with a great white man—now that's funny!"

The comedian was poignant in his remarks to a Washington Post reporter shortly after winning the honor. "I'm a pioneer. That's my contribution. I broke barriers for black comics. I was being Richard Pryor; that was me on that stage. But I was on drugs at the time." Born in Peoria, Illinois in 1940, Pryor grew up in one of his grandmother Marie's string of whorehouses that catered to various black entertainers and vaudeville performers. Pryor developed and honed his comedic skills at an early age as class clown, and later was tapped by mentor, Juliette Whittaker, director on the Carver Community Center in Carver, Illinois as a "fourteen year old genius." She helped to develop his stage and dramatic skills.

A father by 14 and Army vet by 17, Pryor already had a wealth of material from which to draw. Pryor worked the Midwestern chitlin circuit until the early 1960s when he took his show on the road to New York's Greenwich Village, which was in the throes of sociopolitical transition. "A tentative but innovative rapprochement had been established between white audiences and a select group of black comedians," explains journalist and historian Mel Watkins in his book, "On the Real Side" (Simon & Schuster, 1994). "The transitional comics of the fifties (Timmie Rogers, Slappy White, and Nipsey Russell) had made inroads and in varying degrees Dick Gregory, Bill Cosby and Godfrey Cambridge all had bridged the racial impasse." At the time, many black comedians eschewed not only social commentary, but they also tended to mute any fury, or at the very least sanded the edges of the country's racial realities. Pryor, however, dove head first into the deepest of uncharted waters. "African Americans were accepted as clowns and jesters," wrote Watkins, "but were expected to avoid satire and social commentary—the comedy of ideas."

Pryor's breezy act had been modeled upon a then up-and-coming stand-up named Bill Cosby. But with one gesture, in 1967 during a performance at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas, he willfully shattered that mold into tiny, irreparable pieces. He—as the story goes—had an epiphany. Walking off stage mid-act, he went into a self-described exile: "For the first time in my life I had a sense of Richard Pryor the person," he wrote in his autobiography. "I understood myself . . .I knew what I stood for . . . knew what I had to do . . . I had to go back and tell the truth."

And he told it to America's face.

"Richard was always upset with Bill Cosby," comedian and friend Paul Mooney told The Times in a 1995 interview. "I think he wanted to be Bill . . . But I always like Richard's stuff better. Bill didn't wow me. He wowed white people . . . Black people sank into Pryor's material like an easy chair . . . That's what his talent was—talking about black people to black people."

Much of the entertainer's bottomless font of searing observations—social, political, racial—was attributed to his own wrestling with personal demons: a dramatic push-me-pull-you relationship with success within a predominately white industry and his own racial allegiance. "Richard basically blazed a trail for black comedy. He defined what it is. As a young black man he was saying what he felt—and was shocking," comedian Damon Wayans once said.

In his 30 years as a performer, Pryor recorded more than 20 albums, and appeared in more than 40 films, including, "Wild in the Streets" (1968); "You've Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You'll Lose that Beat" (1971); "Hit," "The Mack" and "Uptown Saturday Night" (1974); "The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings," "Car Wash (1976); "Greased Lightning" and "Which Way Is Up?" (1977); "Blue Collar" and "California Suite" (1978); "The Muppet Movie" (1979); "In God We Trust," and "Wholly Moses" (1980); "Bustin' Loose" (1981); "Some Kind of Hero" and "Brewster's Millions" in (1985); "Critical Condition," (1987); "Moving" (1988); "See No Evil, Hear No Evil" and "Harlem Nights" (1989) and "Another You" (1991).

Pryor became the highest paid black performer at the time in 1983 with his $4 million paycheck for "Superman III."

Along with his Grammys, and Emmy, and the Oscar nod, his script for the comedy satire, "Blazing Saddles" written with Mel Brooks, won the American Writers Guild Award and the American Academy of Humor Award in 1974. In those small oases of calm which periodically dotted his life, Pryor was ever changing, reconsidering himself, his choices: A trip to Zimbabwe in 1980, for example, led him to excise his frequent use of "N-word." "There are no niggers here," he wrote in his autobiography. "The people here, they still have their self-respect, their pride."

Struggling with his own sense of pride in another realm, Pryor found himself slowed and increasingly incapacitated in later years as MS took hold. And though he traveled around in a motorized scooter, he continued to write and perform throughout the 90s — one-nighters in the Main Room at Sunset Boulevard's Comedy Store and an episode about MS on CBS' hospital drama "Chicago Hope" which he helped to write and co-starred with daughter, Rain. Pryor, who married six times, is also survived by sons Steven and Richard and daughters Elizabeth and Renee.

Even with the help and therapeutic sparring of ex-wife Jennifer Lee, the disease left the once physically inexhaustible and seemingly insurmountable Pryor immobilized and imprisoned. "The drugs didn't make me funny. God made me funny," he told the Washington Post in 1999. "The drugs kept me up in my imagination. But I felt . . . pathetic afterward . . . . Drugs messed me up."

It was musician Miles Davis who once gave Pryor a key piece of advice during his Village days—"Listen to the music inside your head, Rich. Play with your heart." He did. Until his instrument just wore out.

Source: The Los Angeles Times

1 Comments:

Any issue with performance in an online game is sometimes referred to as "lag" by gamers. However, if your computer's frame rate is low, that isn't the same as lag because the two issues have different root causes. Maximum FPS gives smooth video game experience.

Post a Comment

<< Home