Foiled Once in City, Wal-Mart Turns On the Charm for S.I.

After being rebuffed in its first effort to open a store in New York City, Wal-Mart is trying again, and this time it hopes that Wal-Mart enthusiasts like Sandra Como will flock to its cause. After all, she lives on Staten Island, where the company hopes to build a store.

She frequently crosses state lines to shop at a Wal-Mart in New Jersey. But she does not want one of the company's giant discount stores in her borough.

"If it weren't for all the traffic, I'd be for it," Ms. Como said as she packed boxes of disposable diapers into her Lexus at the Wal-Mart in Woodbridge, N.J., 15 minutes from her home. "But I'd rather come here and not have the extra traffic on Staten Island."

Ms. Como embodies the problem Wal-Mart has encountered as it attempts to scale the fortress walls of New York City, one of the few places in America where its logo cannot be found. In the past month, Wal-Mart has greatly stepped up its efforts to make New Yorkers warm up to it, running radio spots as well as ads in 70 community newspapers. But even in a city that generally takes pride in welcoming outsiders, Wal-Mart is facing a formidable not-in-my-backyard problem.

Whenever there are rumors that the company is contemplating this neighborhood or that, residents begin sounding off that they do not want a super-busy, colossal Wal-Mart near them, with all the expected traffic and pollution. Last February, objections from Queens residents, as well as a storm of opposition from organized labor, helped persuade a major developer to drop Wal-Mart from a large mall planned for Rego Park, Queens.

Despite that setback, executives with Wal-Mart Stores, the nation's largest retailer, say they are looking at other sites in all five boroughs. They say it is time that a company that has 3,762 stores in the United States and opens 250 new stores a year finally has one in the nation's largest city.

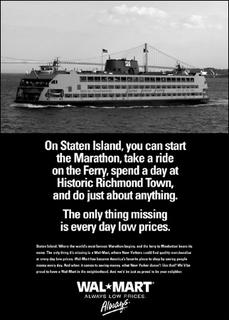

Wal-Mart has sought to bolster its cause with clever advertisements, like a full-page one that ran in The Staten Island Advance. The ad read: "On Staten Island, you can start the Marathon, take a ride on the Ferry, spend a day at Historic Richmond Town, and do just about anything. The only thing missing is every day low prices."

Wal-Mart has plenty of enthusiastic backers, even on Staten Island, where, according to government officials and developers, it hopes to open a store at a former Lucent Technologies factory site in Richmond Valley, on the southern part of the island near the Outerbridge Crossing.

"I'd like to have a Wal-Mart right in New York City," Evelyn Kwakye, a data entry clerk from Staten Island, said while shopping for school supplies at the Woodbridge Wal-Mart. "I'd prefer the convenience, and the price is right also."

Dennis Dell'Angelo, an architect who is president of the Pleasant Plains/Princes' Bay/Richmond Valley Civic Association on Staten Island, said he thought Wal-Mart was focusing its current efforts on his borough because of two factors that might mean less opposition than in other boroughs: it is more suburban and more Republican.

Mr. Dell'Angelo said he believed that if Wal-Mart got its foot in the door on Staten Island, that would make it easier for the retailer to expand into the other, more populous boroughs.

"We need this Wal-Mart like a hole in the head because on the south shore of Staten Island we don't need any more retail whatsoever," he said. "And this is a corporation that has a lot of baggage about how it treats its employees. I hope neighborhoods will consider that before they start welcoming Wal-Mart into their neighborhood."

On a recent afternoon at the Woodbridge Wal-Mart, just three miles from Staten Island and the Outerbridge Crossing, about a quarter of the cars in the parking lot had New York license plates, and a large majority of the New York drivers interviewed said they lived on Staten Island.

While shopping for light bulbs and baby bibs there, Lisa Tortosa, a self-described homemaker from the borough's Annadale section, said she would love a Wal-Mart closer to home. "It would be good for people like my mother, who doesn't drive," she said. Ms. Tortosa dismissed concerns that a new Wal-Mart on Staten Island would generate disconcerting new waves of traffic.

"There's already a lot of traffic in Staten Island," she said. "At least with Wal-Mart, you can go to one store like this to buy everything you need, instead of going to five stores. That might mean people actually drive around less."

Mia Masten, the Wal-Mart official in charge of shepherding its New York hopes into reality, said the company was being singled out unfairly. Wal-Mart's main competitors - Target, Costco, Kohl's and the Home Depot - have received permission to open stores in various boroughs, and she said hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers were eager for Wal-Marts to be built in the city.

"We already know New Yorkers are shopping at our nearby stores, and in fact, last year, New Yorkers spent more than $98 million at our nearby stores," Ms. Masten said, noting that many city residents drove to nearby Wal-Marts in Valley Stream, Westbury and Secaucus. "Our competitors are in New York. They're already successful, and we know it is a viable market for us. And we want to make it more convenient for our customers."

Ms. Masten, Wal-Mart's director of corporate affairs for the eastern region, would not confirm that Wal-Mart was seeking permission to build on Staten Island, saying it had not executed agreements on any site. But developers say Wal-Mart is loath to acknowledge that it is looking at any particular site, not only because that could spur a new explosion of opposition but also because Wal-Mart would be greatly embarrassed if it were seen as losing out at a second New York site.

Ms. Masten said Wal-Mart would bring jobs to New York. "Each store would bring abut 300 jobs, as well as a broad selection of merchandise at everyday low prices," she said. "Why should New Yorkers continue to have to travel to New Jersey or Long Island to shop at our stores?"

But opponents - labor unions, community groups and small businesses - say that Wal-Mart may take away as many jobs as it creates by driving other retailers out of business.

"Wal-Mart would mean a lot of low-end entry-level jobs, and New York City isn't suffering from a lack of entry-level jobs," said Diane J. Savino, a Democratic state senator from Staten Island. "We're suffering from a lack of middle-income jobs and high-end jobs. In addition, Wal-Mart has a reputation as being not just vehemently antiunion but of violating every labor law in the book."

Ms. Masten asserted that small businesses often continued to thrive even after a Wal-Mart opened nearby, noting that Wal-Mart was a general merchandise store. She said that the company's wages and benefits would be competitive. Wal-Mart has acknowledged that some managers have occasionally violated labor laws but said that it vigorously ordered managers to comply with laws and that it disciplined those who violate the laws.

Wal-Mart has 98 stores in New York State and says it pays its workers in the state $10.38 an hour on average. But labor leaders say that Wal-Mart's combined wage and benefits package is at least $6 less an hour than at unionized stores.

On Staten Island, political officials are divided over Wal-Mart, with some siding with consumer interests and others siding with labor unions, small businesses and community groups concerned about traffic.

Borough President James P. Molinaro said he would push for Wal-Mart's approval.

"Anything that develops economic activity in my borough is a good idea - that is, if it's legal and nonpolluting," he said. "And if it gives people place to shop and prevents them from going to New Jersey, it's a good idea. My responsibility is to give half a million people the best possibilities to shop."

Richard Lipsky, the coordinator of the Neighborhood Retail Alliance, the main anti-Wal-Mart coalition in New York, said that the way New York laws are structured, the matter did not come down to how consumers feel.

"You'll find a tremendously high number of people who say, 'They're a good store,' and, 'We go there,' but when you ask them whether they want it in their neighborhood, they say: 'Absolutely not. We don't want to be a magnet for traffic that a store of that size will generate,' " Mr. Lipsky said. "The ultimate decision-making will reflect the site battle more than the generalized goodwill that Wal-Mart can create."

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home